“I Make Envy on Your Disco” — A Q&A With Author Eric Schnall

The Tony Award-winning theatrical producer and marketing director (and Salisbury homeowner) talks about his first novel.

The Tony Award-winning theatrical producer and marketing director (and Salisbury homeowner) talks about his first novel.

“So many people…prefer what was to what is, no matter what the was was.”

This proposition is expressed by a character in Eric Schnall’s first novel, I Make Envy on Your Disco, and hovers over the entire narrative. The plot unfurls in Berlin circa 2003, but the story is as much set in the ether of memory, history, and nostalgia as it is on the streets and buildings of the German capital. Schnall’s protagonist, 37-year-old Sam Singer, compares the city’s energy to the work of an artist admires: “pure and effortless and, to me, profound — the past recorded and transformed, a moment preserved but inverted. And it captures Berlin, or my experience of it — everything becomes something else.”

Sam Singer is a native New Yorker who works as an advisor guiding wealthy art patrons in building their contemporary art collections. He journeys to Berlin to attend a gallery show, "Immediate /Present," about Ostalgie, the German “nostalgia for the products, objects, and way of life that disappeared from [East Germany] almost overnight, after the Wall fell, less than fifteen years” earlier.” But Sam’s story is really about the emotional journey he has undertaken and the life in Manhattan he has temporarily(?) stepped away from.

In a seemingly secure, but stagnant, long-term relationship with Daniel, his architect partner, Sam grapples with impending middle age – what, he wonders, did he really get out of his youth and what does he really want out life going forward? “In New York,” Sam opines of his Gotham ennui, “my entire life is on vibrate.” And so, he ventures out into Berlin to figure out how to make life ring again.

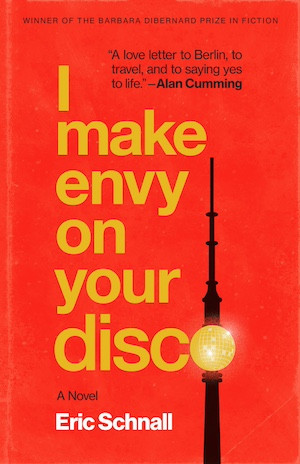

“Novelist” is Eric Schnall’s second career – his first is as a theatrical producer for which he has received a Tony Award for the Broadway revival of "Hedwig and the Angry Inch" and a Lucille Lortel Award for "Fleabag." His debut novel is also being recognized – it won the Barbara DiBernard Prize in Fiction, which is awarded to an LGBTQ+ author whose novel is thought to have commercial potential.

I spoke to Schnall – who has a second home with his partner Shax Riegler in Salisbury, Connecticut, and whose recently-deceased parents had a home there – in April about I Make Envy on Your Disco. Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

I really enjoyed the book – I definitely make envy on your novel. How did it coalesce while you had this other intense career going on?

The book took a long time to marinate. I was in a writing workshop that I joined after September 11th, in New York that was run by a really brilliant novelist, Jennifer Belle. And I was working on another novel. It was about a 12-year-old boy growing up on the Upper East Side in 1982, a version of my own experience as a native New Yorker. I was almost done in about 2003 and then my partner, Shax, said to me we should go to Berlin. He is a magazine editor (now executive editor of Architectural Digest) who has his finger on the pulse of ‘what's next.’ And at that point, Berlin was a very different city than it is now – today, one is expecting it to be this incredibly exciting, vital place. But back then, in 2003, it was still much closer to the collapse of the Wall.

We spent about a week there in October, which is the same month that my book takes place. It was freezing. Like in the novel, there was this spitting, windy, chilly rain, that certainly cast a mood. Everything about Berlin – the clubs, the museum, the art scene, the restaurants – was so exciting, yet rough and ragged. It incited a visceral response in me as someone who grew up in New York City and has seen it go through so many tremendous changes. I was catching Berlin in this moment of deep evolution, reacting to the fall of the Wall even though it was 15 years later. There was so much construction, there was so much renewal, and there was so much of a shift in interest from West Berlin to East Berlin. East Berlin had been something that was off-limits to so many people, both within Germany itself and to the world.

I came back to New York. I was almost done with this other novel. But I was so excited and provoked and inspired by our visit to Berlin, that I went to a coffee shop, and instead of writing the next eight pages for the novel I was completing, the beginning of this story spilled out of me. And then I went through a handful of years where I attempted to finish that first book, but my heart was with this other story. I also returned to Berlin several times in between whatever shows I happened to be working on. I really fell head over heels in love with the city and developed really strong roots in Berlin.

I was lucky enough to have a career working on Broadway and off-Broadway shows, and they were exciting shows. And I was so fortunate to be a part of all of these projects. But I did not, at the time, really see a world in which I could work on a show and work on a book simultaneously. I would try to squirrel in some months between shows in which I could really concentrate on my writing. It wasn't until the past, I don't know, four or six years that I realized that I could do both at the same time.

The protagonist, Sam, is 37 years old. Reading your book now, I'm 25 years past 37.

I'm many years past 37, too.

That’s what I’m getting at. It's a story of a 37-year-old guy, but it seems infused with an awareness of somebody who is older than that, someone who is beyond those experiences. How old were you when you were working on the novel in earnest?

Many ages. Actually, when I began working on what became the novel, I was younger, 33 years old. I don't want to describe myself as an old soul, but I do think that actually some of what you're describing about Sam was just baked inside of me – not in terms of him having wisdom, but in terms of him thinking that life had passed him by and feeling as if as if the road ahead was pretty murky. Sam was actually crankier in previous drafts than he is now, and a bit more world-weary. I toned that down.

We look back now and think, ‘Oh, 37 - what a baby.’ But 37 is particularly an interesting age to write about. It really feels like a transition in which you realize that you are an adult, and you have adult problems, and you have a path to figure out for the next handful of decades. But you're also still so young. In my 30s, I lost touch with that young person. I did feel world-weary. Also, I was so busy working on all these shows, and it was very intense

My attention span is not fantastic. I get bored easily, and I certainly am not somebody who is going to be satisfied with much of anything, including my own writing. But there was something incredibly pleasing about returning to the world of this novel over the years. It was wonderful to go back to Berlin. It was wonderful to go back to a time without iPhones, without social media, where you could truly get lost in a city. Also, it was wonderful to go back in time and, frankly, be 37 again. I never name it in the novel, but the book takes place in 2003. If it were me, literally, Sam would actually be 33. That quality that you're describing in Sam was something that, I guess, existed somewhere within me at an age that was actually younger than Sam.

I think you made a good choice in toning down the bitterness because we've all read novels that are – and this German is from the book - gegen alles, against everything.

Yeah, exactly. Nostalgia is so entirely fascinating because it isn't an accurate representation of what actually was. It is its own recording put through its own filter of what we choose to remember and what we have all accumulated within our individual or collective imagination. When I first experienced Berlin – it was really in the grips of nostalgia, but not everyone was having the same experience. That dichotomy was even more pronounced because the East Berliners and the West Berliners had such completely different experiences for years. The Ostalgie was its own very particular form of nostalgia because there had been a literal separation between the experiences, but a close enough shared proximity.

East Germany had a lot of things that were very problematic. But it was fascinating to consider the dichotomy of pining for things that were lost when the Wall fell, realizing also that those things were the only things available to East Germans. And so, of course, there is going to be a fetishistic longing for all of these traditions and objects and a way of life that disappeared overnight, while also having to reconcile the fact that the reason for the existence of those limited options was very upsetting.

As you put it “everything becomes something else.” Is it a particular characteristic of Berlin?

I think it's a particularly Berlin thing. The history of Berlin over the past 100 years is singular. To have a wall dividing your city, to have the aftermath of World War II, to have all of these things in the not-so-distant past makes it so that multiple versions of history are co-existing right in front of your eyes. I think it's particularly a a Berlin thing; I don't think it's specific to Germany.

Your novel doesn't tie up loose ends, really, and that made it all the more compelling for me. I also was very taken by one quote. Sam is talking about his partner Daniel, and he says, “Lately, when I think about Daniel, I get upset.” He is asked, “Always?” And he answers, “Not always. Well, pretty much, unless I think about the past. But that makes me sad.” That really strikes me as capturing the precise moment where a person is ripe for transformation, the moment where someone is forced to look forward. Was that a very conscious message on your part, or is that just a circumstantial message?

I think it was conscious. I wanted the book to be hopeful. I had written a character who has a lot of things that are not going well back in New York, including his relationship, his lack of enthusiasm for his job, for his home city. There is something about Berlin that wakes him up. I actually was midway through the novel when I came into contact with what became its title, “I make envy on your disco.” I was in Berlin when I heard somebody using that phrase in their clunky German English. I was with a writer friend, and we both thought it was the most amazing thing ever. I kept thinking: “I make envy on your disco. I make envy on your disco.” What if that became the title of my book? And then I thought, well, I have to write a book that fits that title.

And in a way, I liked having that goal because it helped me strike a balance between being dark, and introspective, yet also having more elements of humor than I expected. And also finding pathways towards new beginnings and possibility. All I could hope for is for somebody like yourself to say that they found something in Sam's journey relatable. There's something about this moment in time in this 37-year-old's life that, if I'm lucky, people can glom onto and have some experience with that that relates to their own. And that is just super exciting to me.